(Part 2 of 4) "Gut Primer" Video Series: The two major gut-related pathways for inflammation

Feb 22, 2021This is Part 2 of a free 4-part video series. Part 1 (the gut-immune connection) is here, Part 3 (how autoimmunity happens) is here, and Part 4 (what to do first for your gut) is here.

(Transcribed below)

Welcome back to Part 2 of this 4-part video series on why fixing your gut is synonymous with fixing your immune system.

In Part 1 we talked about the physical relationship between the gut and immune system, and some of the literature that has helped to cement gut dysfunction as a role player in immune disease.

Today we'll take a look at the 2 main culprits for gut-mediated inflammation.

Let's talk for a minute about this big, hefty word: inflammation.

Inflammation is synonymous with chemical immune activity.

Whenever your immune system detects a threat it mobilizes to neutralize it.

The various immune cells in your blood travel to and congregate around the invader, spraying a toxic chemical mixture designed to kill.

This is actually normal and necessary for our bodies to to keep us safe and protected. But problems arise when these processes run amok and never turn off.

Ongoing responses require resources that deplete nutrient stores. This can also make our immune cells more prone to confusion distinguishing between self and not-self. Finally, these ongoing responses work to douse our own tissue in caustic chemicals that can irritate and damage, setting the stage for negative symptom onset.

This ongoing inflammation is what we want to avoid, and is widely agreed upon by the gentlepeople in white coats as the single greatest threat to good health. And it turns out inflammation is largely mediated by the gut, and the two pathways we're about to discuss are the culprits.

There are two systems in the gut that can become altered and result in inflammation.

The first is the microbiome. The composition of microbes that inhabit your intestines is of the utmost importance. It consists of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. In healthy individuals, a carefully curated balance of symbiotic microbes provides heaps of useful services for the body in exchange for accommodation in our guts. More on this in a minute.

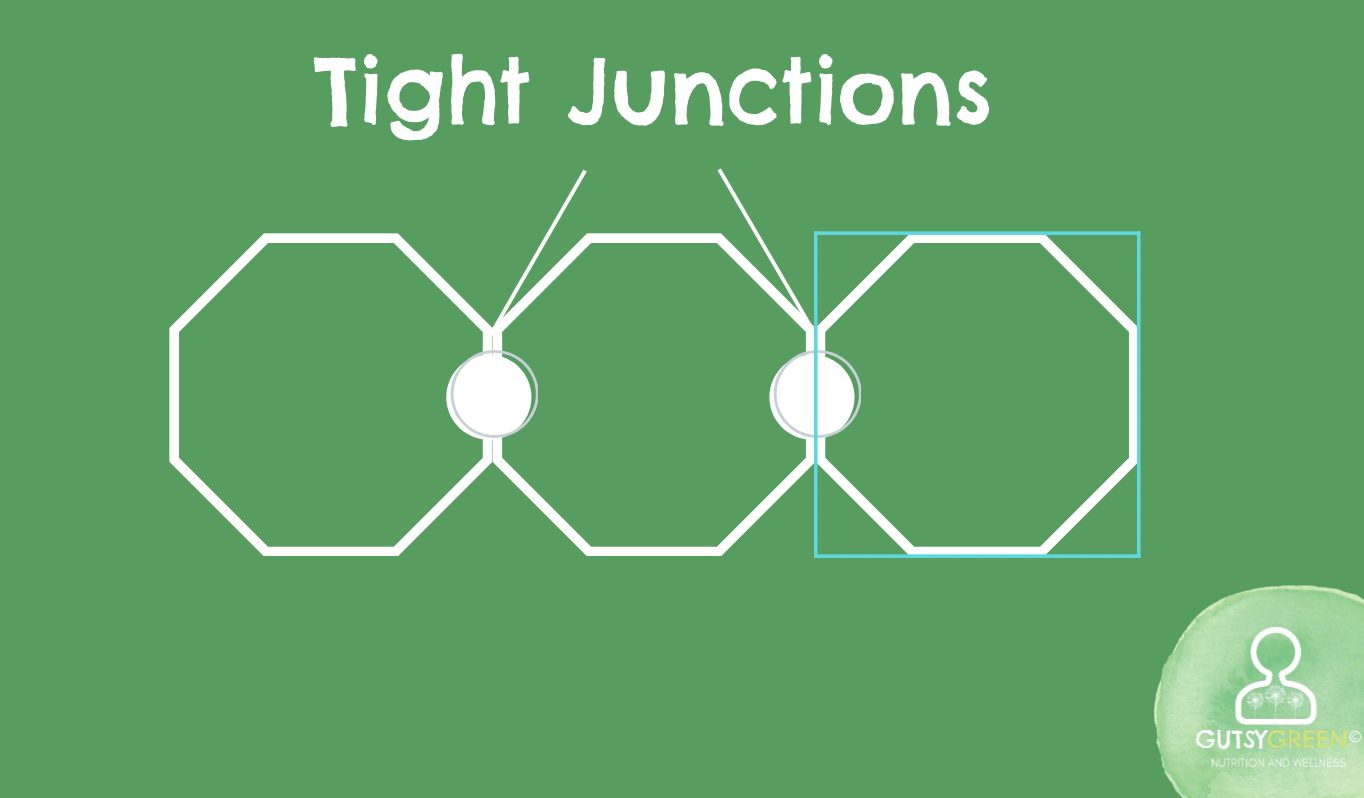

The second way that gut dysfunction manifests is through the epithelium's structural integrity. 'Epithelium' just refers to the tissue that lines the surface of the gut. An ideal epithelium should be robust, and coherent without aberrations or holes in its structure. This is complicated by the fact that the gut's epithelium is only one cell thick to allow for maximal nutrient absorption.

So how do these go wrong?

Our constellation of microbes is sensitive to modern lifestyle conditions, which we'll go into in a moment, but for now all you need to know is that when the composition of your microbiome becomes imbalanced, it's termed 'dysbiosis'.

Intestinal dysbiosis might mean too few good guys, too many bad guys, or a mixture of both. Regardless, dysbioses of all kinds are highly associated in literature with immune dysfunction.

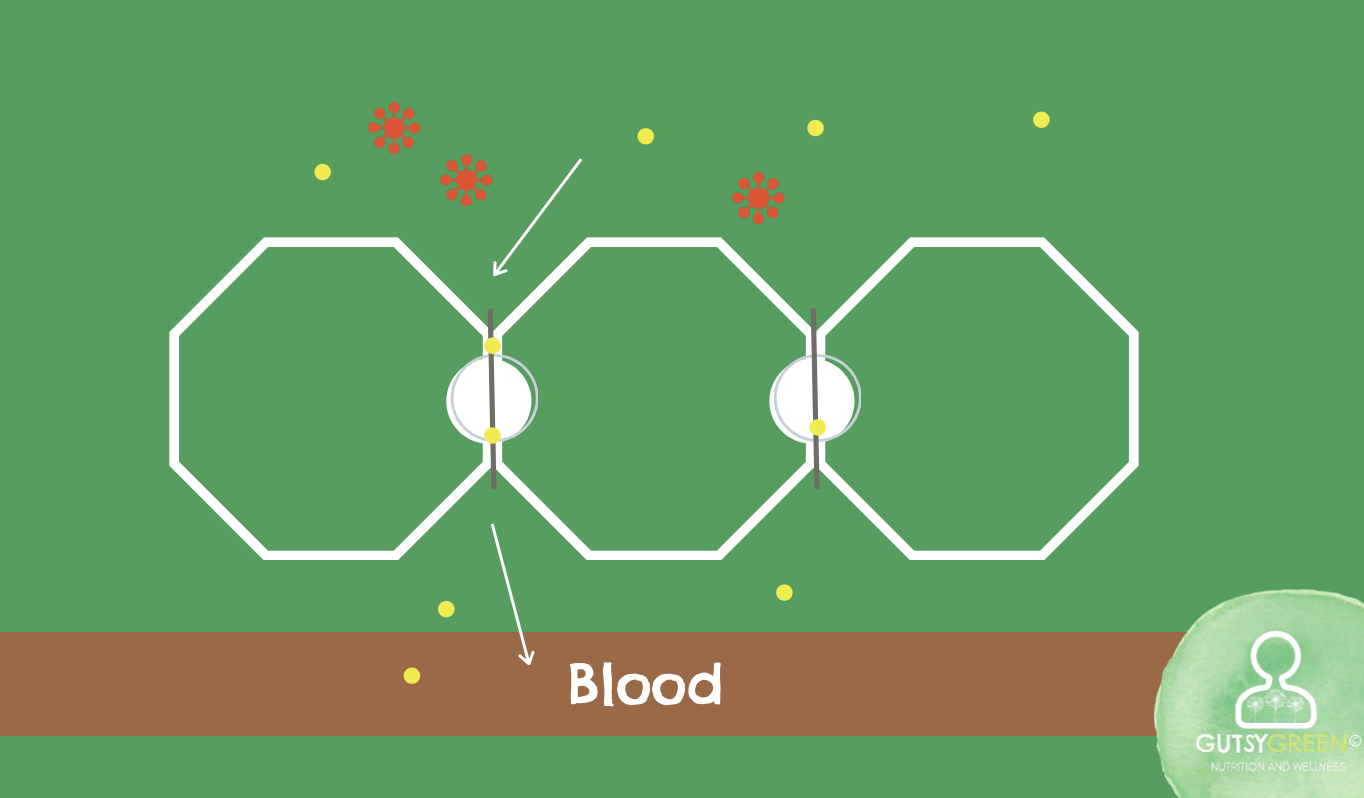

Additionally, when the intestinal lining becomes permeable or "Leaky", inappropriately large molecules from the GI tract are able to enter the blood stream willy nilly.

Usually the process that determines which nutrients get let inside is tightly regulated by a robust cellular structure. In the absence of this, whatever we eat can make its way out into the blood, where its not supposed to be, resulting in our immune system tagging the molecules for destruction, and causing widespread inflammation. We'll talk about how this looks more specifically in Part 3.

So how do these conditions come about? Let's turn our attention to dysbiosis. First, we'll look at two of the most common secondary drivers or contributing factors that lead to dysbiosis. Later, in Part 4, we'll return to this slide and take a look at it again when we discuss the primary driver of dysbiosis.

The first, is a lack of exposure to probiotics or beneficial microbes.

These are ubiquitous in fermented foods such as yogurt or sauerkraut - which are pretty scarce in the Standard American Diet.

They're also found in abundance in nature - which many Americans don't have regular access to.

A lack of good guys also makes us more susceptible to infection from opportunistic microbes.

Think of the gut as a parking lot with a set number of spaces - if the spaces are all occupied by beneficial microbes, there's nowhere for the bad guys to park, and they're forced to move on!

If, however, there's room in the parking lot...

... then they can take up residence on a long term basis, causing chronic issues over time.

Fun fact: If you've ever had a bout of food poisoning and didn't possess sufficient beneficial microbes, you may still have remnants of that event living in your gut!

The second contributor is making improper food choices, usually emphasizing refined carbohydrates and sugars, very common in the standard American diet. When sugars and starches make it to the intestines, they selectively feed opportunist species, and starve beneficial bugs, who prefer low-sugar plant fibers instead.

Dysbiosis can have mild to severe health impacts, but almost always results in higher levels of inflammation in the body due to four consequences.

-

The first is a scarcity of beneficial microbes, as we've discussed. This absence also means an absence of the services these microbes provide such as synthesizing inflammation-quelling B and K vitamins and soothing fatty acids.

-

Lipopolysaccharide is a dangerous end-product produced by pathogenic microbes which can overgrow in the gut. Often abbreviated to LPS, it is also known as 'endotoxin' and is infamous for being one of the most inflammation-promoting substances on record.

-

Nutrient absorption can be impacted by microbes disrupting the absorption structures in the intestine called villi. Nutrient deficiencies impair your body's natural ability to contain inflammation.

-

Lastly, when opportunist microbes colonize, they form a protective layer to live in called a bio-film. These biofilms can loosen 'tight junctions' in the gut.

Tight junctions are responsible for holding together the cells in the gut's epithelium - typically calibrated to allow specific nutrients into the bloodstream through 'driveway' sized channels, These narrow channels act as buffers for any larger compounds, such as pathogens, foreign chemicals, or undigested food particles.

Normal

Leaky

When they are loosened, these driveways become like freeways and allow more inflammatory traffic into the bloodstream. Essentially, this just results in leaky gut.

OK, on to leaky gut's drivers.

Let's take a look at some of the secondary drivers of this condition - how do we get it? With the same promise of returning to these again in Part 4 when we discuss the primary driver behind all of this.

The first is improper nutrition - or failing to ingest the raw materials the body needs in order to repair and strengthen the gut lining.

Usually, this means amino acids from plenty of quality proteins, and the fatty acids from healthy fats. In the Standard American Diet, proteins and fats tend to be processed and inflammatory. Likewise, those who adhere to a plant-based diet will be short on these raw materials.

This goes hand in hand with the second factor, which is ingesting foods you're sensitive to, or that you are unable to digest. When food doesn't properly break down, by the time it gets to the intestines, the sheer size of the food particles can damage the tight junctions and slip into the blood stream, causing inflammation and symptom onset. If this happens often enough then a food sensitivity might even develop!

So, importantly, if our structures are strong and intact, food particles and pathogens stay within the GI-tract where we can easily neutralize and eliminate them.

Think of a castle that is surrounded by a moat.

If invaders come, so long as the moat is deep and plentiful the invaders will not be able to cross it.

A leaky gut would be akin to dropping bridges across the moat for the invaders to use to constantly cross in.

Defenders of the castle may be able to ward them off for a time, but after awhile, without putting the bridges back up, those defenders will become exhausted, and the castle will be in danger.

So, another silly metaphor for why supporting our structures/moats is crucial to resting and normalizing our immune system, and for preventing dangerous pathogenic presences.

You are, essentially, a donut with eyes. We humans are just long tubes. We have this hole that runs from the mouth to the anus. And for the most part, we can think of this tube as being "outside" of the body. Many things enter that tube that we need to keep on the outside because they would hurt us if they entered into our actual tissue. How well we're able to keep these two spaces separate is a *huge* factor for our health.

And so in Part 3 we'll take a closer look at exactly what happens when this goes wrong.

So I hope there are many small brain fires happening in your head right now, and that the rest of the series will begin to stoke them into into a wild blaze of understanding.

Now you know what can happen in your intestines that leads to inflammation.

Next we'll look at how exactly this may lead to autoimmunity or other immune dysregulation.